by SHUBHASHISA AC.

The Shariat law did not do justice to muslim women. Talibanisation was its extreme form. Many moderate muslims claim that such extreme form is a distortion to real essence of Islamic religion.

Whatever is written in Koran Sharif and Hadish becomes a theoretical proposition if in practice women are pushed in a corner and forced to obey the dictum of all powerful priest class. Except some isolated effort by Kamal Pasha in Turkey, Nasser in Egypt, Sukarno in Indonesia and Ayub Khan in Pakistan no serious effort was made to reform Islamic religion synthesising with science, technology, art literature, socio-economic ideas that evolved in last four hundred years. The famous book of Edward Gibbon, ‘Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire’ strongly exposed blind prejudice of Islamic society.

Recently women in many Islamic countries are revolting against the unjust laws and forcing the governments to change those. In Islamic society also struggle for women’s liberation is a long painful chapter. The social scientist

of Morokko, Fatima Marnissi narrated the struggle in her books, ‘The Veil and the Male elite’, ‘ A Feminist Interpretation of Women’s Rights in Islam’; Islam and Democracy and ‘Beyond the Veil’. After the second world war women sneaked into the universities in the Middle East countries. According to Marnissi, ‘Only the university and education provided a legitimate way out of mediocrity.’ In Tunisia, in Egypt, a big number of women struggled to enter the university. In Egypt, the rise of the fundamentalist and the rise of feminist movement happened simultaneously. How feminism became so strong in that environment? They declared,’ Opposition taught us to practise the politics of the ‘tireless pen’… that is the more police ban, the more must be written.’ That means if one writing is banned seven more should be written within 24 hours. Even facing mass imprisonment and torture they declared ‘The mosque and the Koran belong to women as much as to heavenly bodies. We have a right to all that, to all its riches for constructing our modern identity.’

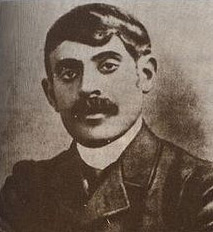

The Egyptian jurist and one of the founders of the Egyptian national movement and Cairo University (Wikipedia)

The modern movement of Islamic feminism began in the late nineteenth century. Egyptian jurist Qasim Amin, the author of the 1899 pioneering book Women’s Liberation (Tahrir al-Mar’a), is often described as the father of the Egyptian feminist movement. In his work, Amin criticized some of the practices prevalent in his society at the time, such as Polygamy, the veil and purdah, i.e: sex segregation in Islam. He condemned them as un-Islamic and contradictory to the true spirit of Islam. His work had an enormous influence on women’s political movements throughout the Islamic and Arab world.

In recent times the concept of Islamic feminism has grown further, with Islamic groups looking to mobilise support from as many aspects of society as possible, and educated Muslim women striving to articulate their role in society. It has been, however, mainly upper-middle-class women , that have been able to vocalise the Islamic feminist movement, as they have the economic power to violate widely held beliefs.

Exploring Islamic Feminism, Margot Badran, writes: “Islamic feminism, a phenomenon that became increasingly discernable in the 1990s, continues to spread following the turn of the new century. At this still early stage, it is useful to map the contours of emergent Islamic feminism”.

It is a global phenomenon that is not restricted to any geographical region. Its bravest campaigns have been conducted in Asia and Africa, while some of the boldest discursive articulations of Islamic feminism have appeared in the diaspora and convert communities in the West.

If Islamic feminism is a recent phenomenon, Islam and feminism have an association dating back to the 1890s. At that time, Egypt was an important pioneering site of feminism in the Muslim world, where what would later be recognized as a “feminist consciousness” arose in the context of encounters with modernity. Muslim women and men used Islamic reformist arguments to break the linkage of Islam with repressive practices imposed in the name of religion. This paved the way for changes in women’s lives and in the relations between sexes. Soon feminism became enmeshed in the rising discourse of secular nationalism which called for equal rights of all Egyptians, be they Muslim or Christian, in a free and independent nation. In short, feminism and Islam were allies.

Islamic feminism, like the secular nationalist feminism of its day, is a product of its time. Islamic feminism appeared on the scene in the wake of the spread of Islamism, or political Islam, and with the broader ascendancy of an Islamic religious and cultural revival. An examination of popular and scholarly literature leads to a basic definition of Islamic feminism as a feminism anchored in the discourse of Islam with the Qur’an as its central text, and exegesis as its main methodology. The core idea of Islamic feminism is the full equality of all Muslims, male and female alike, in both the public and private spheres.

Islamic feminism is more radical than secular feminism which called for equal rights in the public sphere but complimentary rights in the private sphere. Concerning the public sphere, Islamic feminists argue that women may be heads of state and imams, a claim that secular feminists never advanced. In the private sphere, Islamic feminists are challenging the conventional notion of male authority over females in marriage and the family. Islamic feminists also call upon all Muslims, including men, to live by the egalitarianism of Islam, something secular feminism side-stepped.

Although research and general observation indicate that the term “Islamic feminism” is coming into increasing use, its circulation is still limited and both the term and the idea remain controversial. It is also important to make a distinction therefore between Islamic feminism as a discourse, a mode of gender analysis, or an ideology, and Islamic feminist as an identity. Most of those who participate in the shaping of what can be viewed as “Islamic feminism” do not claim an Islamic feminist identity. There are indications, however, that there is some movement towards explicit acknowledgement of Islamic feminism. The shapers of Islamic feminism include the following three groups: those who are more fully oriented towards Islam (sometimes called “committed Muslims”), secular feminists, and former leftists.

Islamic feminism is manifested both as a global or universalist core set of ideas and as specific local forms of activism with their own particular needs and priorities. The Internet facilitates the dissemination of Islamic feminism’s core ideas and the spread of information about local forms of activism. Examples of local forms of Islamic feminist activism include demands for women to hold the positions of judge, mufti (officials who issues religious rulings), and ma`dhun (an official who register marriages) in Egypt. Another example is the demand by both men and women in South Africa that women be permitted to share the main mosque space in parallel groups rather than being relegated to the back or an upper floor during congregational prayer. As the intellectual discourse of Islamic Feminism spreads, so too will these localized forms of activism.”

Another side to modern Islamic feminism is the activism of Muslim women born and brought up within Western societies. Often those born to immigrant families face racism from the host community and sexism within their own communities. Young Muslim women in France fought back against the issues facing them, ranging from endemic sexual violenceto the forced wearing of the hijab, by creating Ni Putes Ni Soumises (usually translated “Neither Whores Nor Submissives”). This movement has spread to other countries.

Islamic feminist like their western counterpart also demanding universal suffrage, human rights and access to education and medical care.

Muslim Personal Law (also known as Muslim Family Law) that includes the areas of law: marriage. divorce, and testation has also been challenged by the Islamic feminists.

Muslim majority countries that have promulgated some form of MPL include Saudi Arabia, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Libya, Sudan, Senegal, Tunisia, Egypt, Indonesia, and Bangladesh. Muslim minority countries that already have operating MPL regimes or are considering passing legislation on aspects of MPL include India and South Africa. Islamic feminists in these countries have serious objection in such legislation in those countries.

Many Islamic feminists demand that MPL should not just be reformed but should be rejected and that Muslim women should seek redress, instead, from the civil laws of those states.

For most Islamic feminists, some of the thorny issues regarding the way in which MPL has thus far been formulated include: polygamy, divorce, custody of children, maintenance and marital property. In addition, there are also more macro issues regarding the underlying assumptions of such legislation, for example, the assumption of the man as head of the household.

Another issue that concerns Muslim women is the dress code expected of them. In some cultures such as Afghanistan and Saudi Arabia they are expected to wear the all-covering burqa or abaya; in others, such as Tunisia and Turkey they are forbidden to wear even the headscarf (often known as the hijab) in public buildings. Muslim feminists resist both extremes of externally imposed control. But in non Muslim countries many women wears hijab as political jesture against the critical view of such use by non Muslims and as a show of solidarity with Islam.

It should be commented here that whatever interpretation one can make, Islam had framed a secondary role for women whether in family matter, or religious and social matter. Without transcending religious dogma itself to a humanistic religion, women’s freedom will remain a distant dream. Feminist leaders like Taslima Nasrin of Bangladesh and similar counterpart in other Islamic countries will have to live under threat or persecution.