Ac. Krtashivananda

Liberal Journalism, And Climate Deceptions

In an era of permanent war, economic meltdown and climate ‘weirdness”, we need all the champions of truth and justice that we can find. But where are they? What happened to trade unions, the green movement, human rights groups, campaigning newspapers, peace activists, strong-minded academics, progressive voices?

We are awash in state and corporate propaganda, with the ‘liberal’ media a key cog in the apparatus. We are hemmed in by the powerful forces of greed, profit and control. We are struggling to get by, never mind flourish as human beings. We are subject to increasingly insecure, poorly-paid and unfulfilling employment, the slashing of the welfare system, the erosion of civil rights, and even the criminalisation of protest and dissent.

The pillars of a genuinely liberal society have been so weakened, if not destroyed, that we are essentially living under a system of corporate totalitarianism.

The anaemic liberal class continues to assert, despite ample evidence to the contrary, that human freedom and equality can be achieved through the charade of electoral politics and constitutional reform. It refuses to acknowledge the corporate domination of traditional democratic channels for ensuring broad participatory power. This pretence afflicts all the major western ‘democracies’.

But, of course, corporate media professionals have long propped up the illusion that the public is offered an ‘impartial’ selection of facts, opinions and perspectives from which any individual can derive a well-informed world view. Simply put, ‘impartiality’ is what the establishment says is impartial.

The journalist and broadcaster Brian Walden once said: ‘The demand for impartiality is too jealously promoted by the political parties themselves. They count balance in seconds and monitor it with stopwatches.’ This nonsense suggests that media ‘impartiality’ means that one major political party receives identical, or at least similar, coverage to another. But when all the major political parties have almost identical views on all the important issues, barring small tactical differences, how can this possibly be deemed to constitute genuine impartiality?

The major political parties offer no real choice. They all represent essentially the same interests crushing any moves towards meaningful public participation in the shaping of policy; or towards genuine concern for all members of society, particularly the weak and the vulnerable.

The essential truth was explained by political scientist Thomas Ferguson in his book Golden Rule . When major backers of political parties and elections agree on an issue – such as international ‘free trade’ agreements, maintaining a massive ‘defence’ budget or refusing to make the necessary cuts in greenhouse gas emissions – then the parties will not compete on that issue, even though the public might desire a real alternative.

In many respects we now live in a society that is only formally democratic, as the great mass of citizens have minimal say on the major public issues of the day, and such issues are scarcely debated at all in any meaningful sense in the electoral arena.

The public recognises much of this for what it is. Opinion polls indicate the distrust they feel for politicians and business leaders, as well as the journalists who all too frequently channel uncritical reporting on politics and business. A 2009 survey by the polling company Ipsos MORI found that only 13 per cent of the British public trust politicians to tell the truth: the lowest rating in 25 years. Business leaders were trusted by just 25 per cent of the public, while journalists languished at 22 per cent.

And yet recall that when Lord Justice Leveson published his long-awaited report into ‘the culture, practices and ethics of the British press’ on November 29, he made the ludicrous assertion that ‘the British press – I repeat, all of it – serves the country very well for the vast majority of the time.’

That tells us much about the nature and value of his government-appointed inquiry.

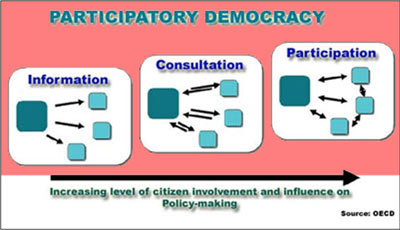

Whereas Participatory democracy is a process emphasizing the broad involvement of constituents in the direction and operation of political systems. While etymological roots imply that all governments deserving the name “democracy” would rely on the participation of their citizens (the Greek demos and kratos combine to suggest that “the people rule”), traditional representative democracies tend to limit citizen participation to voting, leaving the main work of governance to a professional political elite. Participatory democracy strives to create opportunities for all members of a political group to make meaningful contributions to decision making, and seeks to broaden the range of people who have access to such opportunities.

Whereas Participatory democracy is a process emphasizing the broad involvement of constituents in the direction and operation of political systems. While etymological roots imply that all governments deserving the name “democracy” would rely on the participation of their citizens (the Greek demos and kratos combine to suggest that “the people rule”), traditional representative democracies tend to limit citizen participation to voting, leaving the main work of governance to a professional political elite. Participatory democracy strives to create opportunities for all members of a political group to make meaningful contributions to decision making, and seeks to broaden the range of people who have access to such opportunities.

All theories of green politics include some variant of participatory methods. In these theories, of which the best known is the Four Pillars of the Green Party, making consultation on important decisions by those who will carry it out reduces the probability of a decision that seriously disadvantages one group (reducing social justice) or of violent resistance (breaking nonviolence). Expressing ecological wisdom in law, for instance, is not likely to be respected unless the persons who live near protected ecosystems help to carry out the decision on a daily basis. Efforts to redefine green politics to exclude the participatory and consensus decision making methods have historically failed.

Source: Media Lens—David Cromwell